Legislation

Brazil is acknowledged to be an important player on the environmental stage. Since the Rio Earth Summit of 1992, no major international debate on the issue has taken place without Brazil being present; Brazil has played an active role in the negotiation and development of multilateral instruments.

As one of the world’s largest food producers, Brazil demonstrates that it is possible to produce and preserve.

Brazil’s environmental legislation is among the world’s most modern and comprehensive, starting with the Constitution, which enshrines every individual’s right to enjoy an ecologically balanced environment—understood to be a shared asset that is essential to quality of life; it is therefore the duty of the government and of society to protect it and preserve it for present and future generations.

The Brazilian Constitution also includes other legal instruments whose goal is to protect the environment, such as the need to conduct Environmental Impact studies, create protected areas, comply with environmental permission processes, and implement a system of civil, criminal and administrative accountability in the event of failure to comply with the law.

Overall, the main legal instruments are environmental permits, mandatory for activities that use natural resources or that are deemed to be potentially or actually polluting or harmful in terms of environmental degradation. Preliminary environmental impact studies and environmental impact reports are mandatory in the case of activities that significantly impact the environment.

Brazilian legislation involves several documents and players. Among the main federal environmental agencies we can list IBAMA (The Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources—Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis), which is responsible for enforcing environmental legislation and granting environmental permits for activities in strategic places; ICMBio (The Chico Mendes Biodiversity Conservation Institute—Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade), which is responsible for managing and applying legislation in federally-protected areas; CONAMA (National Council for the Environment—Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente), which is a body of technical experts overseeing approvals for important environmental rules; CGEN (Council for the Management of the Genetic Heritage—Conselho de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético), which is responsible for regulating, monitoring and implementing rules for the management of genetic heritage; and CNBS (National Biosecurity Council—Conselho Nacional de Biossegurança), which is responsible for approving the commercial use of GMOs on the basis of recommendations put forward by CTNBio (National Technical Commission for Biosecurity—Comissão Técnica Nacional de Biossegurança).

In addition to federal agencies there are also state- and municipal-level agencies that issue environmental permits and inspect and apply sanctions in the event of environmental damage in their jurisdictions.

In the State of São Paulo, CETESB (Environmental Company of the State of São Paulo—Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo) is responsible for the control, inspection, monitoring and licensing of polluting activities: its main remit is to preserve and recover the quality of water, air and soil.

Highlights of Brazilian legislation

Brazil has had forest protection and preservation legislation since 1965. The New Forest Act was passed into law in 2012, maintaining the core concepts of permanent preservation areas (PPAs) and legal reserves.

Permanent preservation areas are areas that must be protected because of their location and physical and geographical characteristics: hilltops and riverbanks, for example. Legal reserves are a percentage of the area of farms on which native vegetation must be maintained as coverage in order to contribute (along with the PPAs) to the preservation of biodiversity and ensure the economic and sustainable use of natural resources. Brazil currently boasts a real-time deforestation and slash-and-burn detection system.

CAR (Rural Environmental Registry—Cadastro Ambiental Rural), a mandatory public registry of all rural properties, containing the farm’s geo-tagged information and thus delimiting permanent preservation areas and legal reserves, was set up in 2012. It is an important instrument for carrying out environmental diagnoses and corrections. The registry data will make up part of SICAR (National Rural Environmental Registry System—Sistema Nacional de Cadastro Ambiental Rural), which will be managed by each state’s environmental secretariat, alongside the Ministry of the Environment and IBAMA.

Brazilians landowners have until May 2016 to register.

Complying with the legislation

Failure to comply with Brazilian environmental legislation leads to penalties ranging from warnings and fines to the banning of activities. Fines can be very heavy, depending on the type of violation, the culprits are expected to recover the affected areas. More than sixty different environmental crimes are contained in the criminal legislation, and punishments range from fines to imprisonment without bail for those found guilty.

All federal, state and local environmental agencies have the power to inspect and apply sanctions when violations of the legislation are committed within their jurisdictions. The Federal Police, the Highway Police and the National Guard coordinate to carry out the inspections.

The citrus-growing industry’s concern for the environment

With only 0.7% of arable land under oranges, Brazil produces roughly 50% of the world’s orange juice.

The industry is also a leader in adopting best practices and in pursuing constant improvement, seeking to meet the demands of consumers in more than 70 importing markets.

Among highlights in the environmental area we may mention:

- Rational land use

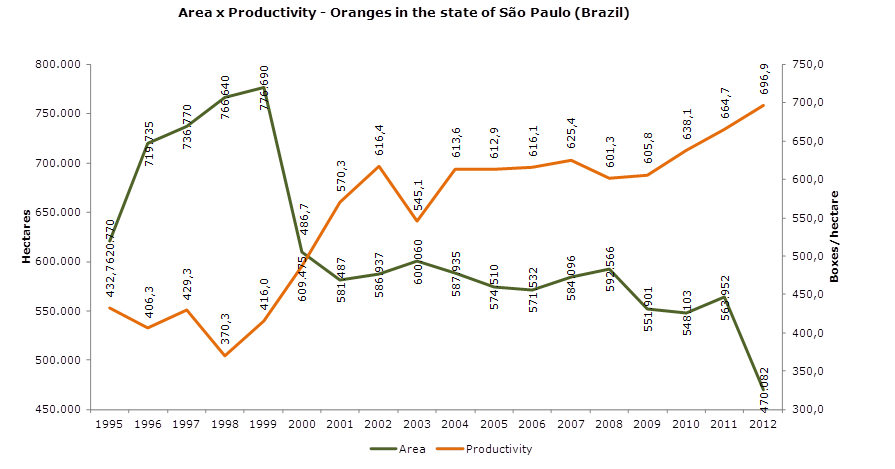

Over time the industry has reduced the area of land it occupies without affecting output. Yield has grown from 15 tonnes per hectare to 29 tonnes per hectare in Brazilian orange orchards over the last 15 years, with technological innovations in irrigation, fertilization, suitable soil use and higher tree density. The sector prioritizes the occupation of areas already degraded and the productivity has increased in the last years, while the occupied area has decreased, according to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE):

- Production Systems

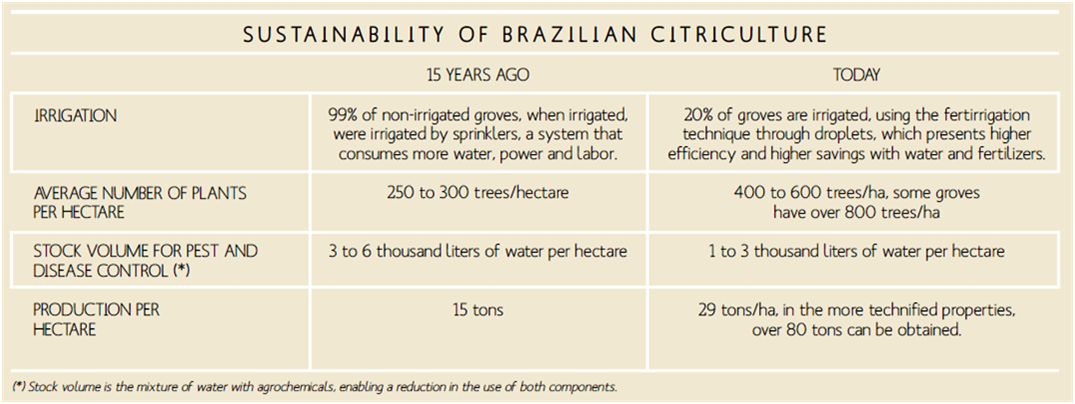

Through innovations and research, the industry has enhanced its production systems in recent years. Compared to 15 years ago, we can see major changes in the number of trees per hectare, the proportion of irrigated trees (and the irrigation techniques themselves), and the volume of liquid used to control pests, for example.

These improvements have been achieved thanks to investments by growers, research institutes, companies and other players in Brazil’s production chain.

- Rational water use

In companies producing orange juice, almost 75% of the volume of water needed for industrial processes comes from the oranges themselves, and is removed in the juice concentration process. This reduces the need to take water from the supply system.

Nonetheless, in its pursuit of continuous improvement, the sustainability committee of CitrusBR—an association representing the major companies—carried out a pilot study in 2011 on water use in order to map out possible vulnerabilities and improve its practices.

- Transforming residues

The juice-producing industry uses every part of the orange. The rind, seeds and pulp become by-products such as essential oils and animal feed, and are used by other industries.

Additionally, companies have recycling programs in their factories.

- Rational use of plant protection products

As with other crops around the world, orange plantations are vulnerable to pests that affect the orchards and cause diseases in the fruit, such as the greening, the citrus canker, the citrus sudden death and others.

In Brazil, the Ministry of Agriculture (MAPA), the Ministry of Health, and ANVISA (National Sanitary Surveillance Agency) work together to approve or ban the use of plant protection products (PPPs) in Brazilian orchards, and regulate their use.

The AGROFIT list published by MAPA contains the active ingredients allowed for use on citrus crops: they are approved after presenting all the necessary studies and documentation.

It is an extensive list because it takes into consideration only those plant protection products used in Brazil without accounting for the legislation of countries that may import the produce.

Since Brazil’s orange juice industry exports most of its production, a shorter list (PIC—the Integrated Citrus Production list) was created by the Fundecitrus Agricultural Chemicals Committee, taking into consideration the need for strict compliance with the legislation of the major importing markets.

Growers intending to supply the industry with fruit must take the PIC list into consideration when planning their activities. Processing companies attach the list to their fruit-sourcing contracts in order to ensure that only permitted active ingredients are used in orange growing.

The Fundecitrus agricultural chemicals committee comprises representatives of growers, plant protection product manufacturers, companies and research institutes, meeting normally every three or four months to reassess the PIC list. For a product to be included on the list, it must be approved by Brazil’s Ministry of Agriculture and be registered or possess an MRL in the main markets.

In 2014, the AGROFIT list contained 118 PPPs for use with citrus fruit, while the PIC list contained 55 PPPs.

In recent years there has been an increase in the use of PPPs in orchards in order to fight such blights as greening, which is transmitted by an insect and thus requires the application of insecticides. However, growers seek permanently to keep quantities used to the minimum. In the case of greening, Brazil is a benchmark for other countries affected by the blight: such practices as regional control by coordinated applications of PPPs makes it possible to use fewer applications, in turn increasingly effective themselves. Another highlight is the Fundecitrus project for biological control of the psyllids that transmit the disease.

The sale of PPPs is controlled in Brazil—a trained professional must issue a prescription: thus banned PPPs may not be used, nor the wrong quantities of the right ones.

Over time products have been developed that are more specific and more selective, as well as less harmful to workers and to the environment. The use of PPEs is nonetheless mandatory.

The fruit delivered to the juice factories undergoes testing and controls to identify the use of banned PPPs. Exported orange juice also undergoes analysis for the same reason.

- GHG emissions

The sustainability committee of CitrusBR—which represents the main juice-making companies—has been studying the industry’s carbon footprint since 2009, including orchards and juice terminals in Europe.

The goal is to find points for improvement and understand vulnerabilities in a range of variables that affect orange-growing and juice-production.